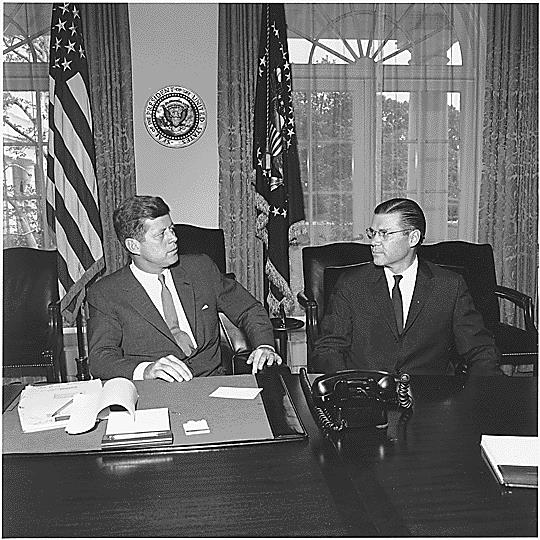

Elected in 1960, John F. Kennedy (1917-1963) became the 35th president of the United States. He served from 1961 until his assassination in November 1963. Despite the warn of Eisenhower about Laos and Vietnam, the opinion of J.F. Kennedy about Europe and Latin America was much more important than that in Asia. The administration of Kennedy remained crucially devoted to the Cold War foreign policy which was inherited from the administrations of Truman and Eisenhower. In 1961, Kennedy had to cope with the failure of the Bay of Pigs Invasion, the Berlin Wall’s construction, and the negotiation between Pathet Lao communist movement and the pro-Western Lao government which was seen as a threefold crisis. John F. Kennedy believed that the U.S credibility with allies and his reputation would be seriously damaged by another failure of controlling and preventing the expansion of communism. Thus, he decided to “draw a line in the sand” and stop the widespread communism in Vietnam.

In May 1961, Lyndon B. Johnson, the U.S Vice President paid a visit to Saigon. In this visit, the U.S Vice President ardently honored Ngo Dinh Diem as the “Winston Churchill” of Asia. The reason for this title was that Diem was the “only boy” qualified. Johnson pledged to support more aid to Diem’s regime in order to resist the development of communism in Vietnam. The policy of Kennedy applied in South Vietnam depended much on the belief that Diem regime could finally defeat the rebellion of communists. However, the South Vietnamese military quality was still poor with poor leadership, corruption, and political promotions which triggered the weakness of the South Vietnamese Army. The guerrilla offensives in the south of Vietnam broke more frequently. That if the Soviet space and missile programs surpassed those of the U.S or not was a main concern of Kennedy. Although he concentrated on a comprehensive missile in the equality to the Soviets, Kennedy was also lured into using special forces for preventing insurrections of communists in Third World countries. He believed that it would be effective when applying guerrilla tactics of these special forces for a “brush fire” war in Vietnam. In April 1962, Kennedy was warned by John Kenneth Galbraith that the United States might follow the failure of the French. John F. Kennedy still increased the U.S troops in the Southern Vietnam. By 1963, there were 16,000 American military personnel in South Vietnam. In 1961, the Strategic Hamlet Program started. By this program, the joint U.S and South Vietnamese tried to relocate the rural population into fortified camps.

On January 2, 1963, the Battle of Ap Bac typically marked the series of failure of the incompetent performance of the South Vietnamese Army. James Gibson, a historian described briefly about the situation: “Strategic hamlets had failed…. The South Vietnamese regime was incapable of winning the peasantry because of its class base among landlords. Indeed, there was no longer a ‘regime’ in the sense of a relatively stable political alliance and functioning bureaucracy. Instead, civil government and military operations had virtually ceased. The National Liberation Front had made great progress and was close to declaring provisional revolutionary governments in large areas.” In the Battle of Ap Bac, the Army of Vietnam was led by Huynh Van Cao, the most trusted general commander of the IV Corps under Diem regime. As being a Catholic, Huynh Van Cao was promoted for his religion and fidelity, not his skill. His major duty was to preserve his forces to fend off overthrows. During this time, Ngo Dinh Diem was judged by some policymakers in Washington that he was not able to defeat the widespread of communism and might negotiate with Ho Chi Minh. Between 1960 and 1962, Diem became more suspicious, which attributed to U.S encouragement.

In May 1963, after being banned to display religious flags during the Buddha’s birthday celebration, Buddhists rose up in South Vietnam. Many Buddhist demonstrators were shot by South Vietnamese police and army troops. At this time, the administration of Kennedy was blamed for the trouble in Vietnam, as he backed simpleton Diem regime. Many news photographers captured the sacrifices of the Buddhists, which psychologically shock American public and Kennedy. Responding to the situation of deepening unrest, Diem imposed martial law. On August 21, 1963, Colonel Le Quang Trung and Ngo Dinh Nhu (Diem’s younger brother) led the Army of Vietnam Special Forces to raid pagodas nationwide, which resulted in the widespread damage and destruction. In the middle of 1963, a regime change was discussed by U.S officials; in this discussion, the United States Department of States encouraged a coup, while the Defense Department supported Diem. After that, Ngo Dinh Diem was murdered. Diem regime was put an end with his execution along with his brother on November 2, 1963.

After the overthrow, South Vietnam was in the political instability, which created favorable condition for Hanoi to increase its support for the guerrillas. U.S military advisors were entrenched by the South Vietnamese armed forces. In Washington, the military leadership was antagonistic to any role for U.S advisors other than conventional troop training.